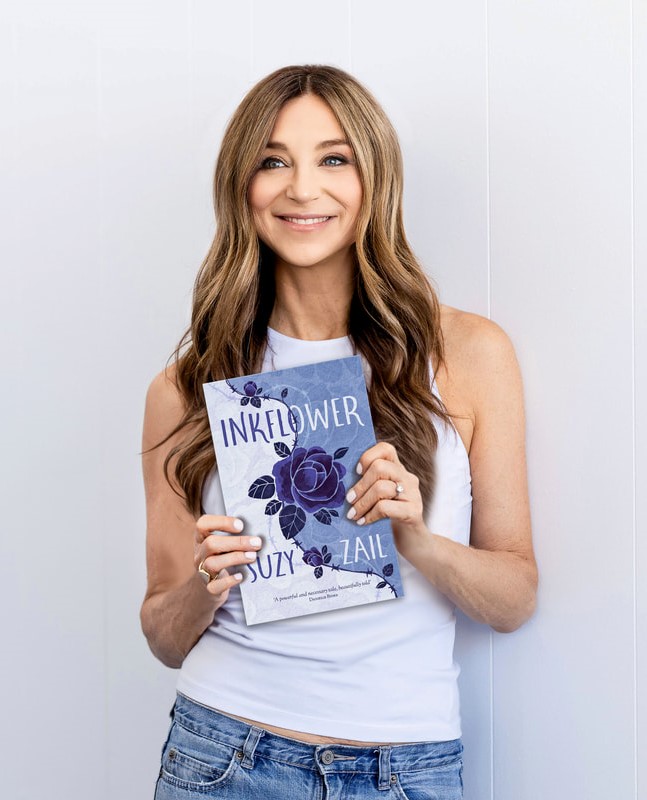

Meet Suzy Zail, author of Inkflower – Book Links 2024 Award for Children’s Historical Fiction Shortlist

By Mia Macrossan

There are three brilliant writers on this year’s Book Links Children’s Historical Fiction Award Shortlist:

Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky by Rebecca Lim, A & U Children, 2023.

The Fortune Maker by Catherine Norton, Harper Collins, 2023.

Inkflower by Suzy Zail, Walker Books, 2023.

All three are outstanding for their perceptive writing, immediate appeal, and the sensitive way they present complex issues for younger readers. They succeed above and beyond in increasing the understanding and appreciation of history by children.

Each author has kindly agreed to answer a few questions about writing historical fiction for StoryLinks.

Today we interview Suzy Zail

Today we interview Suzy Zail

Suzy Zail used to be a lawyer but quit to become a writer. Her books include The Tattooed Flower, The Wrong Boy, and Alexander Altman A10567 – all stories based on or inspired by her own Jewish heritage. Inkflower is the powerful story of Lisa, a teenage girl who finds out her father has six months to live. He uses the time he has left to tell his family about his time in Auschwitz, something he has kept hidden until now. It’s based on Zail’s own father’s experiences as a child survivor. The story alternates between her father’s account of his war experiences and Lisa’s life in the 80s.

You say on your website that your father’s story started you writing. You say Inkflower is ‘the truest thing I’ve ever written and very timely.’ Could you expand on that?

Inkflower is the story of a girl who finds out her father has six months to live and a secret he hasn’t told her about his time in Auschwitz. I say it’s the truest thing I’ve ever written because that girl is me. When I was thirty-two, my father was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease and given six months to live. Until then, he’d kept his Holocaust story from us because he didn’t want that chapter of his life to be our personal inheritance. But like Lisa’s dad, he finally told us the story after he was diagnosed.

Everything that happens to Lisa’s father in Inkflower, mirrors events in my father’s life, and all the lessons Lisa learns while watching her father die, are lessons my father taught me. Writing Lisa’s story forced me to revisit that most harrowing, beautiful and transformative time in my life and excavate my feelings. I’d been taught as a child, to let go of sadness and look toward the future, not back. But that’s the thing about writing a 16-year-old; you have to feel all the feels, because at 16, everything is momentous and unbearable.

And so, for the first time since my father died, I gave myself permission to feel. To sit with the story and unpick it. I sat at my desk being Lisa, and finally let myself come undone.

I say the book is ‘timely’ because it came out twenty years after my father died, and felt like a beautiful tribute. But timely too, because messages about war and the dangers of unchecked hate are needed now, more than ever.

You also wrote your father’s story in the memoir, The Tattooed Flower. What made you decide to revisit this material and create a book for young adults?

My father taught me that we have to talk about the things that scare us before we can change them. What happened to my father when he was a kid scared me, and it made me angry. The fact that nothing had changed in the two decades since I’d written The Tattooed Flower, and that we were still hurting each other, scared me too. And what do you do with all that fear and anger? Revenge is nice but change is better. And who better to target than teenagers, who are still working out who they are, and what sort of world they want to live in.

As a writer, my best weapons are words, so I returned to my father’s Holocaust story to create something healing. A book that lets us hold onto hope and move closer to a world in which we all feel safe.

Fictionalising the story and re-imagining it for a Young Adult readership was a gift. It gave me the freedom to imagine the places and people my father had mentioned only fleetingly, and make them 3D, to guess at the feelings he left unexamined and fill in the gaps. It allowed me to create a character who has her own secrets – no one at school knows Lisa is Jewish, or that her dad is dying. Making her someone who is uncomfortable about her father’s disability, and their shared history, allowed me to teach Lisa, and the reader, important truths about love and acceptance, and how to let people in.

The beauty about fiction is you can direct the action. I could make Lisa struggle, fail, learn, grow, have setbacks and grow again throughout the novel, and use that to tell a different kind of truth. And tell it in a way that will capture young readers. The writer, Richard Powers once said: ‘the best arguments in the world won’t change a single mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.’ I hope, with Inkflower, I’ve done that.

In writing a novel, where does characterization start? You say that creating characters was ‘a steep learning curve…imagining them into existence, giving them a voice and a personality, having them laugh, cry, love, starve and sometimes die.’ The characters in Inkflower certainly do a lot of that. Tell us about Lisa and her friends, is she based on you?

In writing a novel, where does characterization start? You say that creating characters was ‘a steep learning curve…imagining them into existence, giving them a voice and a personality, having them laugh, cry, love, starve and sometimes die.’ The characters in Inkflower certainly do a lot of that. Tell us about Lisa and her friends, is she based on you?

I’d written three YA novels before Inkflower and with each of them, I’d started with a character prompt-sheet, a place where I put down everything I know about the character before I begin writing – their eye colour, favourite food, what frightens them, their level of education, the name of their best friend, their prejudices, fears and goals. What do they most want? And what’s stopping them from getting it? I never get to use all of this in my books, but the time I spend here lets me get to know my characters and guess at how they might put sentences together and react to situations.

My books are always inspired by real events or people, so research plays a big part in characterization. With The Wrong Boy, a story about a 16-year-old pianist who plays for the Commandant of Auschwitz, I spent hours listening to classical music, studying my character’s favourite composers and reading about the real Auschwitz-Birkenau women’s orchestra. With I Am Change I went to Uganda to spend time with young girls. Their stories and their hunger to learn gave Lilian, the main character, depth and authenticity.

With Inkflower, I had a head-start. It was easy to imagine Lisa’s house – I’d grown up in it – and being a teenager in the 1980’s; I was. I hadn’t gone to Glenrock Secondary and I wasn’t seventeen when my father died, but I knew how it felt to lose a parent, and be the child of a survivor who’d kept his past secret. I knew what it felt like to want to fit in, to be someone who felt uncomfortable in the spotlight, someone who preferred to listen, rather than speak. Someone who sensed it wasn’t safe to be a Jew.

All I had to do was recall those feelings and blow them up. I made Lisa more angsty, more secretive about her father’s past, and more conflicted about his growing disability.

That set-up allowed Lisa to grow alongside her father, as both learn to be vulnerable and let people in. I could also have Lisa do the things I wish I’d been brave enough to do, like wash and feed my father in his last months. I’d been scared, so I’d avoided it. Lisa was scared of her father’s frailty too, but I made her push through that fear. She’s me, but she’s braver.

Lisa, the main character is living in the 80s, which is forty years ago, ages away for young readers today. You obviously had a lot of fun researching that time period and you include many fascinating details. How did you manage to make Lisa and her friends appeal to contemporary readers but still stay true to the period?

It was great fun researching what to clothe Lisa in, what music to put in her ears, what foods she’d crave, what posters to put up on her bedroom walls. The 80s was a place my readers and I could escape to when the war chapters got heavy, but they were as foreign a time for teen readers as 1940’s Europe. That didn’t worry me. Kids like being dumped in unfamiliar worlds. They want to visit places they haven’t been to – physically and emotionally. As long as there are characters they can relate to there.

I think Lisa and her friends appeal to teen readers because they want what all teenagers want. And that’s to be safe and loved. To fit in and be in control of their own story. Not have a secret past foisted on them, or have a parent up and die. Contemporary teen readers connect to Lisa and her father because they know what it means to be lonely and scared. And they want to learn, at a safe distance, how other kids get through it. They relate to Lisa because I made her real. She’s not always brave, generous and kind. She’s complex and flawed. She doubts herself and she make mistakes, just like the rest of us.

Katrina Nannestad says of her World War 2 books that adults reading them find them more harrowing than the intended child readers. Lisa’s father’s account of his war experience is harrowing, almost relentlessly so. How did you decide what to include, what to say, and how to say it?

When my father finally told us his story, he didn’t cry or get emotional. It was almost like he was on the outside looking in. He was still protecting himself, and us too. He talked about hunger not starvation, death instead of murder.

I don’t shy away from making readers feel deeply, but like my father, I’m careful to protect my teen readers. And so I didn’t recount my father’s story exactly as it was told to me. Or relay everything I’d read and seen while researching the Holocaust. I held back on the graphic detail and braided moments of light through the dark. Hope is a huge thing in YA literature and all my books are infused with it. In the Holocaust chapters, there are always good people who perform small acts of kindness. And then there’s the camaraderie of the prisoners, a kind guard and brave neighbours, and the rebuilding of lives after liberation. In Lisa’s world, there are friendships, days at school, make out sessions with her boyfriend, 1980’s hair and Duran Duran.

I think it’s okay for kids to be uncomfortable when they’re reading. Bending the world to shield them from their fears doesn’t help them overcome those fears. But there are many ways to tell a story and I found that, if I concentrated on my protagonists’ internal worlds, I could still tell the truth without frightening my readers.

It’s a delicate balancing act. I know Inkflower might make my readers sad at times, but reading about the Holocaust might also teach them something about history and hatred, so that next time they see prejudice they might be moved to act.

Inkflower is a story that resonates long in the mind after reading, as it is rich in important themes. What is the most important thing you would like readers to take away from reading Inkflower?

Wow, it’s hard to narrow it down to one. I learned so many things in the last years of my Dad’s life that I hoped to pass on, through Inkflower, lessons like: ‘Sharing your fears, shrinks them’ and ‘Being vulnerable, takes guts.’ Also, ‘Small acts of kindness can be hugely powerful.’ During the war, my dad had been saved by the kindness of strangers, time and again.

And ‘Celebrate today’. That was a big one for my Dad. Every time he lost some functioning –the ability to feed himself or walk – he’d find something else to make life worthwhile, the fact he could still swallow, and sit in his wheelchair and watch his grandchildren race up the stairs when they visited after school.

But if I have to pick one, it’s probably: Being different is okay; being different should be celebrated.

Can you tell us a little bit about the next book we can expect from you?

I’m working on the final draft now, so hopefully it won’t be too long before my next YA novel is on shelves. Like my others, this one is about a teenager grappling to hold on to the person she was, before an unexpected event shattered her perfect life. In this case a diagnosis.

I guess I’m still writing about difference. Maybe I haven’t let my father’s story go. Maybe I’m still trying to transform it into something beautiful, something that might drive change. I think my Dad would like that.

Thank you so much Suzy, for taking the time to answer our questions. It is always fascinating to gain a deeper insight into a writer and her craft.

Go to Suzy’s website for more information about Suzy and her work.