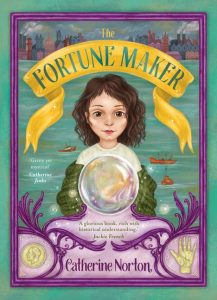

Meet Catherine Norton, author of The Fortune Maker – Book Links 2024 Award for Children’s Historical Fiction Shortlist

By Mia Macrossan

There are three brilliant writers on this year’s Book Links Children’s Historical Fiction Award Shortlist:

Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky by Rebecca Lim, A & U Children, 2023.

The Fortune Maker by Catherine Norton, Harper Collins, 2023.

Inkflower by Suzy Zail, Walker Books, 2023.

All three are outstanding for their perceptive writing, immediate appeal, and the sensitive way they present complex issues for younger readers. They succeed above and beyond in increasing the understanding and appreciation of history by children.

Each author has kindly agreed to answer a few questions about writing historical fiction for StoryLinks.

Today we interview Catherine Norton, author of The Fortune Maker.

Today we interview Catherine Norton, author of The Fortune Maker.

Catherine’s first book, Crossing, was joint winner of the Patricia Wrightson Prize in the 2015 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. It was also a CBCA Notable Book. She was born in the UK but grew up mostly in Adelaide, where she now lives. Of her writing she says: ‘ I write stories for kids who love page-turning adventure, history and a touch of magic.’

Why do you write historical fiction?

I have always loved reading it, for the way it can take me to a different time and place. I don’t think people who lived in previous eras were the same as us in every way – they thought differently, they knew and believed different things, they understood their place in the world differently to us – but in some ways they were just like us. They loved, struggled, wondered and worried and did the best they could with the lives they had. I enjoy putting myself in the shoes of people in the past and wondering what it might have been like to experience what they experienced. But I’m much more interested in everyday people and their lives than the political machinations of important historical figures. I also appreciate the freedom historical fiction has to interrogate our assumptions about the past and to tell stories left out of the history books – it can be quite a subversive art form in that regard.

During this period, the early 20th century, spiritualism and seances were very popular among the high and the low. Was that partly the inspiration for this remarkable story?

Funnily enough, not at all. I kind of came up with the idea that people could see the future as a distinct idea, then played around with the historical setting until I hit on the right point in time for the other elements of the story to work, which have more to do with WW1 and science than early 20 th century spiritualism. The truth is, humans have always believed weird things and looked for answers in strange places, and we still do today.

You have three interesting and contrasting characters in this story: Maud, coming up from grinding poverty but with a special ability, Eleanor, coming from a life of privilege wanting to become a chemist; and Caroline, educated working class, an idealistic suffragette. Each one could have been the central character. What made you decide on Maud?

You have three interesting and contrasting characters in this story: Maud, coming up from grinding poverty but with a special ability, Eleanor, coming from a life of privilege wanting to become a chemist; and Caroline, educated working class, an idealistic suffragette. Each one could have been the central character. What made you decide on Maud?

I love this question! Eleanor in particular was a very insistent character, popping up all the time when I was writing, wanting to tell her story. There was a point at which I wondered if it was hers. But there are more than enough novels about privileged characters and their lives and not enough stories about people like Maud. My own family during that era was not privileged – some were from a background like Caroline’s and some lived in poverty – and their world fascinates me. Caroline was never a contender for protagonist – to my mind, she’s a classic supporting character, although I’m glad you think her fully-formed enough to have a novel of her own!

Each one of your characters embodies an aspect of that historical period – even including Mrs Wray and the poor woman who wanted to find out that she was not pregnant. Tell us a bit more about Eleanor and Caroline and how you create your characters.

I’m always interested in the lives of women and how they have navigated and defied the patriarchy across different historical periods. And going back to my earlier point, we tell so many stories about privileged people in history that it’s easy to form a view of the past in which women embroidered endlessly and sat around waiting to get married. That wasn’t true at all for working class women, who have always worked,and who often did paid work as well as the hard labour of running a household. So the different characters are an attempt to convey – and honour – some of the varying experiences of women at that time and the fact that they were all up against diverse and sometimes complicated challenges. The reality is that having a baby, for example, is a different prospect if you live in grinding poverty than if you live in a huge house with servants, regardless of how much you love your children, and women aren’t all going to feel the same way about everything.

This book has such a strong sense of time and place. I know you did a lot of research as the story is rich with details. Did a house really sink into the ground in the Silvertown slums? Is there a tunnel under the Thames full of psychics? How did you decide what to include/exclude in the novel. What historical flavour did you aim for?

A house didn’t sink into the Silvertown bog as far as I know, but it is a real place, and at that time it was a terrible slum. It did smell as awful as I describe in the book, being next to factories that made soap and fertiliser. A chemical factory in Silvertown was requisitioned in the war and exploded in 1917, flattening houses in the surrounding area and killing lots of people. The explosion was so big that debris was found on the other side of the Thames. That seeded the idea for Maud’s foretelling about the Empire Dye Factory. The tunnel is real, but has never been full of psychics! I learnt about it when I was looking at Thames river crossings and the years they were built, trying to figure out how Maud would have crossed at different points in the story (I didn’t want to send her across a bridge that wasn’t actually built until 1924, for example). The Woolwich foot tunnel opened in 1910. I went there last year and it is quite spooky. Up to that point I’d imagined my Seers’ market in a maze of backstreets somewhere, but decided it would be more fun to put it in the tunnel.

It is so hard not to include too much in a historical novel. You have to keep an eye on what serves the story, and you don’t want the reader to wade through too much detail, so you inevitably leave out lots of fascinating things. At the same time, the more you research and become familiar with a period in history, the more you forget what is common versus specialised knowledge. So you have to be careful not to leave crucial things out, either. Luckily, those sorts of things will usually come up in the editorial process.

In terms of flavour, I grew up reading a lot of early- to mid-twentieth-century English children’s classics. I was inspired by the narrative voices in those books, which draw you in at the first sentence and have you completely entranced by the end of the first page. Children, they say, let me tell you a story. They often begin with an arrival – of the children to a new place, or of somebody new into the children’s lives. A lot of contemporary novels go for something quite different – an explosive hook, a dramatic exchange between characters. I like to set the scene a bit. I don’t ultimately think The Fortune Maker sounds like the ones I grew up reading, but it was a starting point for me in terms of craft. I’m also more interested in the real world than completely made-up ones, but I’m not averse to a bit of fantasy, so I chose to include a magic element in an otherwise realist setting – with a bit of storybook exaggeration, of course.

I love the phrase from your blog ‘Stories begin a new way of seeing’. As well as being an action packed read this story is rich in important themes, grief, loss, education for women, suffragette movement, gender roles and more. What would you like readersto take away from reading it?

It’s true – stories are thought experiments. They ask, what if? This is a story about hope. What keeps us striving and fighting for a better world? What gets us up in the morning? Kids today live in very uncertain times, which can be frightening, but uncertainty is also what opens the way for hope. Without uncertainty there’s no possibility – good or bad.

Can you tell us a little bit about the next book we can expect from you?

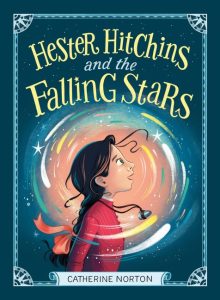

Hester Hitchins and the Falling Stars is out from HarperCollins in just a couple of months, August 2024. It’s another historical novel for middle grade readers, set in England again, but this time it’s 1866. Hester Hitchins’ father is lost at sea and she wants to learn how to navigate so that she can find him. But in 1866 this means learning astronomy too. It’s about a time in history when we were discovering all sorts of things about our place in the universe, and what that meant for a clever young girl who isn’t supposed to expect much from the world. This story doesn’t have any magic in it but it does have a giant telescope, a spectacular meteor storm and a cast of very colourful characters who I had a lot of fun writing about.

Hester Hitchins and the Falling Stars is out from HarperCollins in just a couple of months, August 2024. It’s another historical novel for middle grade readers, set in England again, but this time it’s 1866. Hester Hitchins’ father is lost at sea and she wants to learn how to navigate so that she can find him. But in 1866 this means learning astronomy too. It’s about a time in history when we were discovering all sorts of things about our place in the universe, and what that meant for a clever young girl who isn’t supposed to expect much from the world. This story doesn’t have any magic in it but it does have a giant telescope, a spectacular meteor storm and a cast of very colourful characters who I had a lot of fun writing about.

Thank you so much for talking to StoryLinks.