Meet Rebecca Lim, author of Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky – Book Links 2024 Children’s Historical Fiction award shortlist

By Mia Macrossan

There are three brilliant writers on this year’s Book Links Children’s Historical Fiction Award Shortlist:

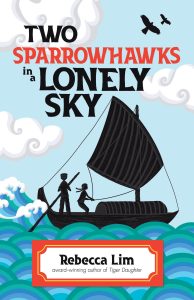

Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky by Rebecca Lim, A & U Children, 2023.

The Fortune Maker by Catherine Norton, Harper Collins, 2023.

Inkflower by Suzy Zail, Walker Books, 2023.

All three are outstanding for their perceptive writing, immediate appeal, and the sensitive way they present complex issues for younger readers. They succeed above and beyond in increasing the understanding and appreciation of history by children.

Each author has kindly agreed to answer a few questions about writing historical fiction for StoryLinks.

Today we interview Rebecca Lim, author of Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky

Rebecca Lim is an Australian writer, illustrator and editor and the author of over twenty books, including Tiger Daughter (CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers and Victorian Premier’s Literary Award-winner), The Astrologer’s Daughter (A Kirkus Best Book and CBCA Notable Book) and the picture book Our Family Dragon A Lunar New Year Story. She is a co-founder of the Voices from the Intersection initiative and co-editor of Meet Me at the Intersection, a groundbreaking anthology of YA #OwnVoice memoir, poetry and fiction.

Rebecca Lim is an Australian writer, illustrator and editor and the author of over twenty books, including Tiger Daughter (CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers and Victorian Premier’s Literary Award-winner), The Astrologer’s Daughter (A Kirkus Best Book and CBCA Notable Book) and the picture book Our Family Dragon A Lunar New Year Story. She is a co-founder of the Voices from the Intersection initiative and co-editor of Meet Me at the Intersection, a groundbreaking anthology of YA #OwnVoice memoir, poetry and fiction.

It is such an evocative title, how did you come up with it and why sparrowhawks?

Like Fu and Pei, Chinese Sparrowhawks are native to Southern China and they are“common”, but tough and hardy. I wanted to set something tiny, relatively powerless and local to a specific area against the fearsomeness and vastness of the wider world (signified by the “lonely sky”) and posit whether such a creature would survive if displaced from its familiar environment.

Why do write historical novels? Do you think it is important for children to read serious historical novels like this one?

Building empathy, asking readers to walk in another’s shoes, is one of my guidingprinciples when I write stories for children and young adults. So whether I’m writing stories with supernatural/paranormal, crime, mystery, contemporary and/or historical elements, I’m asking readers to leave their comfort zone and see and feel what the characters in my stories are seeing and feeling. I’m actually not known as a writer of historical books. I’m probably more properly recognised as a fantasy or spec fic writer. But another one of my personal projects is to set the record a little straighter with regard to our “canon” of published Australianchildren’s books, and to broaden the notion of what it means to be “Australian.” I grew up in Australia in the 1970s and 1980s and never saw people like me in books for kids. For most of the 20 th century (ie into the late 1990s), our published books for children and young adults did not feature migrants from a non-British, non-European background (like me) written by people from non-British or non-European backgrounds, let alone reflect our rich First Nations cultures. They simply didn’t. So it’s very important to tell younger readers that this country already had many people, from many different First Nations cultures, living in it when the British colonised it, and it’s also been built (both before and after Federation in 1901) by migrants from a multitude of non-white backgrounds. And because of abhorrent policies like the “White Australia Policy” (an actual thing from 1901 to circa 1973, when it was finally officially dismantled), stories about First Nations peoples and these “other” migrants were simply not told because they were considered unworthy, or inconsistent with the “Britisher” nation-building narrative.

So, besides hopefully being a stirring tale of adventure, Two Sparrowhawks also functions as a corrective, a thought experiment, and an elegy for a lost era in which Asian-Australian voices were denigrated, unwelcome and unheard. Imagine being legally/politically/socially unwelcome in this country — as people like Fu and Pei were during the years the novel is set (1951 – 1958) — but losing everything you love and own in a small village in China and having to try to make your way to Australia anyway, despite the laws and policies, because your last surviving family member is there. I am asking readers to feel the impossibility and enormity of this, yet root for these two children (children like them underneath) to make it.

You say in your Author’s Note that ‘a book like this…would not have been accepted for publication in the years in which the story is set.’ P293. Do you think enough people, schools and publishers are ready now for this kind of story or is there more to do?

You say in your Author’s Note that ‘a book like this…would not have been accepted for publication in the years in which the story is set.’ P293. Do you think enough people, schools and publishers are ready now for this kind of story or is there more to do?

There is so much more to do. I’m currently doing a PhD on who was writing stories that were published in Australia for “Australian” children during the height of the White Australia Policy (circa 1901 – 1959) and the early results are quietly devastating. While many of the books published during that period are no longer in print (possibly because of that un-nuanced, very unsophisticated to the 21 st -century eye, “Britisher-over-all” narrative), they were foundational to much of our 20 th century output, our concept of what was “Australian” or an “Australian child”, and that dataset I’m combing through (including Awards data for the period against ABS population data) is just … depressing. Whether it was publishers or tastemakers who weren’t ready for this kind of story, the population itself, or all of the above, it’s hard to say. But stories like Two Sparrowhawks weren’t being published and the one Asian-Australian author (born and bred in New South Wales) I am aware of that was working in 1947 simply does not appear in the official dataset of published-in- Australia, “Australian” authors for the above period I’m looking at. So either people weren’t ready for this kind of story back then, or someone made that decision for them within the overarching milieu of the White Australia Policy. Whether people, schools and publishers are ready now for this kind of story I leave up to the universe — this is my own contribution to truth-telling and correcting the record for Asian-Australians who never saw themselves in official 20 th century narratives in this country, but who contributed to what this nation is today, despite massive obstacles being placed in their way. Where did Australia’s Chinatowns, josshouses and Chinese-language gravestones come from? All those stories are just …gone, lost.

You say ‘our published landscape of books for children and young adults is poorer for all those lost years …’ p 293. What stories are we still not telling that need to be told?

In a recent radio interview, the interviewer asked me, “Do children’s books particularly talk about the British immigration story … I’m sort of struggling to think of what I read as a child” and I pointed out that there’s a silence at the heart of the things we learn as children at school, including Federation, the Gold Rush, the Eureka Stockade, Gallipoli, that centres one kind of Australian and Australian story over all others. Our national identity and narrative are very much built on one kind of rugged “Australian” and our national myths are quite one-sided and un-nuanced for that reason. “Others” were there, and in the case of our First Peoples, they were always there, but our published landscape of children’s books, indeed, our origin story, discounts, demonises or downplays, Australians who failed to meet the accepted mythology. All I will ask you to do is to re-read Dot and the Kangaroo (as originally published) as a thinking, questioning adult, and to recall that The Magic Pudding was

created by a Chinese cook called “Curry and Rice” (!) who was murdered by Bill Barnacle, the sailor, and Sam Sawnoff, the penguin, so that the two of them could take possession of the pudding and go on their adventures.We haven’t even begun to tell the stories of all of the Australians who built and contributed to our modern nation. Two Sparrowhawks is my attempt to “de-colonialise” our published children’s book canon (not “decolonise”, as I recognise that I am also a colonist).

The story is a revelation for many readers about immigrants and marginalised people who struggle to survive, sadly very timely at the moment. This could have been a riveting adult novel. Why do you think it is important to tell this particular story to children?

Children are our hope and our future. If you want to build a thinking, feeling, responsible citizen of the world, and a society that values empathy, kindness and compassion over empty commercialism, greed, aggression and ambition, we need to trust that our children will want to be part of truth telling, and will want to recognise and fight injustices, and seek to correct them as adults. I would have loved a story like this as a child because as a migrant child, I saw people like me as the “villain” in stories around Federation, the Eureka Stockade and the Gold Rush, and completely absent from national institutions such as Gallipoli, politics, sport and the arts, even though Asian-Australians have been documented as living here since the early 19 th century (quite leaving aside trade and relations between Asia and those living on this continent in the centuries before that).

The story provides a rich kaleidoscope of characters, good, bad and in between. The unexpected kindness of strangers is a thread throughout the book. Is this an important theme for you or was it a way of moving the story along?

The kindness of strangers has been a huge thread in my life — people I will never meet and thank in person have kept a loved one alive in the street long enough forthem to survive. Kindness — doing kindness/paying it forward and recognising it in others — is a major theme of my life, so it’s always going to be a major theme in my stories. I really believe that what you give out to the universe is what you are gifted in return. Kindness is never a deus ex machina in my stories, it’s very much at the heart of everything. Kindness, just like unkindness, ripples outward into many lives. Iknow which ripples I’d rather be subjected to, and I’m constantly asking younger readers to consider it too. Do you want to be a destructive force? Or a force forgood? What would you do, if this were you?

The book is full of stand out characters but for me Cadre Ling was fascinating. (I think she deserves her own book). How do you go about developing and creating your characters?

This very much sounds woo-woo, but when I’m researching anything that I’m working on, the universe simply provides. I went down many rabbit holes for Two Sparrowhawks and stumbled across a historical female figure (a daughter of a high-ranking Communist party leader of the era) who was also an astro-physicist. You can’t make this kind of amazing stuff up. I just thought immediately, She’s my girl, and Cadre Ling was born.

Two Sparrowhawks in a Lonely Sky is a story that resonates long in the mind after reading, as it is rich in important themes. What is the most important thing youwould like readers to take away from reading it?

That we need to constantly challenge ourselves and see things from outside our own narrow perspective. The ‘lightbulb moment’ for many kids is that sudden realisation that not everyone is like you and shares your lived experiences. I believe that the moment you realise that, it makes you a better human. History is cyclical and constantly repeats, and Two Sparrowhawks is seeking to show how far we’ve come as a nation, but also how much farther we have to go. For example, refugees are still dying or being incarcerated or deported when they take to the seas, hoping to reach safety here. In that sense, Two Sparrowhawks isn’t fiction at all. For many, coming here is actually the difference between life and death.

Can you tell us a little bit about the next book we can expect from you?

I’ve got about four spec fic things on the go, for middle grade through to adult readers, and gladiator-style, one of them will eventually rise!

Thank you so much for talking to StoryLinks.

The winner of the 2024 Book Links award for Children’s Historical Fiction

will be announced at a special free online event on 17 July via ZOOM.

BOOK HERE

Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Pingback: Rebecca Lim wins the 2024 Book Links Award for Children’s Historical Fiction – Story Links