Maree Coote talks about writing historical fiction

‘Historical fiction can also be the telling of a true story—based on real events—that is lifted it out of its time to reset the story as a universal tale. Born in history, immortalised in story.’

‘Historical fiction can also be the telling of a true story—based on real events—that is lifted it out of its time to reset the story as a universal tale. Born in history, immortalised in story.’

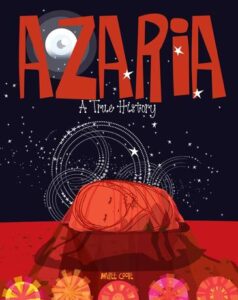

Maree Coote is a writer, designer, illustrator, photographer and publisher. Maree is passionate about a sense of place and history, and she brings this to life in multiple platforms for multiple audiences. She publishes original books through her company Melbournestyle including her much awarded picture book, Azaria: A True History, the story of the abduction of Azaria by a dingo and the subsequent miscarriage of justice as Lindy Chamberlain is accused, convicted, and imprisoned for her murder. The book is shortlisted for the Book Links Award for Historical Fiction for Children

‘A remarkably crafted retelling of the loss of baby Azaria Chamberlain and what can happen in the minds and hearts of Australians when fiction becomes more important than fact.’ Judges’ comments.

Maree kindly agreed to talk to StoryLinks about her approach to historical writing.

What is historical fiction to you and why do you write it?

‘Historical fiction’ means different things to different writers and readers.

Often, historical fiction is story-telling in which the plot is primarily fictional, but the time period in which it is set is both particular and palpable, and can even become another character that plays a powerful role in forming the story’s events, its tone and its outcomes.

But for me, in this instance, historical fiction can also be the telling of a true story—based on real events—that is lifted it out of its time to reset the story as a universal tale. Retold in a ‘de-factualised’ way, the plot-line can be elevated away from the awkwardness of chronology. This is how real events are transformed into myth and folktale, rounded off and simplified by repetition over the ages into the most salient details, like like Hansel and Gretel, or even like Indigenous songlines. It’s how we make meaning in the world. Born in history, immortalised in story.

Why did you choose this particular time/topic?

Why did you choose this particular time/topic?

I can always identify my many motivations for choosing this topic of Azaria’s story, but I think the story ultimately chose me.

I simply couldn’t forget it. The images it conjured in my kind became artworks over the years. The story had all the archetypal characters that people a fairy tale: Mother, babe, wolf, wilderness, cruel king, angry mob… it was already a folk-tale, waiting to be written.

Firstly, I remember when the real event occurred, and at that time I had my own experiences of Uluru and of dingos. I remember the media reports, and I knew the characterisations of Lindy Chamberlain and dingos were not correct. I always felt that a great injustice was being done and it rankled with my sense of fairness. I was extremely disappointed in our authorities at the time, who I felt presided over a gross miscarriage of justice for all the wrong reasons of arrogance, ignorance and expedience.

Writers can, and sometimes do, champion the causes of others, and this is such a project. I was really trying to right a wrong. To stand for the innocent. There were many people who suffered in this injustice, not least the Indigenous peoples. The family at the heart of the story was unnecessarily further traumatised by their treatment at the hands of the government and its agencies, the media and the law. Even the wildlife was pilloried.

I was also very aware that although this tragic event happened 40 years ago, it is still happening regularly today with wild dingos—although more often on Fraser Island than at Uluru. The great tragedy of the original story meant that people had turned away from it, and that was erasing it from our national awareness. There was an inherent danger in this. And it seemed impossible to let this enormous lesson slide away after so many had paid such a high price.

And finally, I think children need to see adults (through the medium of story tellers) stand up and acknowledge where we got things wrong in the past. It demonstrates that we are accountable, and that mistakes can be fixed, which is a great and healing lesson.

How do you reconcile truth and fiction in your historical writing?

Facts tell us what happened.

Fiction puts us in the shoes of those it happened to. It makes the protagonists real. It helps us understand how and why things unfolded as they did. It amplifies characters, motives, emotions and choices, so we can empathise and hopefully better understand the forces that were in play as events unfolded.

Sometimes, in the telling of history, fiction can be ’truer’ than non-fiction. In non-fiction, there can be legal considerations that limit or obfuscate. Sometimes the real flow of events can be obscured just by serving chronological accuracy. But in fiction, one can be perhaps less accurate but more meaningful. For me, serving the truth is inextricable in historical fiction – indeed truth is the only real reason to tell history in any genre. Otherwise we have nothing to stand on. Nor can we learn.

Who is your favourite writer of historical fiction? What is it about them that you admire?

Dickens’ works were all set some 30 years before his own lifetime, so if I can exploit a technicality, I choose Dickens. But, in terms of Australian writers of historical fiction for kids, it would have to be Jackie French. Her output is simply phenomenal, and her aim is to remind us that history matters.

What is next for you?

Next for me in this area of children’s historical fiction will be the story of a fearless, fabulous pioneer in environmental science. The story is both extraordinary and simple, and I think many will relate to such a life. I cannot tell you more, because I’m still writing— the book is in the oven, and if I open the door too soon, it may not rise!

Thank you so much for the invitation to explain my work. I deeply appreciate the opportunity, and I hope both the book and my comments bring interest to readers, writers and teachers.

Thank you, Maree for your thoughtful and inspiring comments.

The winner of the inaugural Book Links Award for Historical Fiction for Children will be announced on Saturday 16 October from 4:00 – 4:45pm via ZOOM, free admission. Book here.

Mia Macrossan

Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Pingback: Maree Coote talks about writing historical fiction – Book Links QLD Inc

Pingback: ‘Born in history, immortalised in story.’ Six award winning writers reveal how they write historical fiction – Story Links