Meg McKinlay talks about writing historical fiction

‘When I’m drawn to historical fiction, I think it’s because of the empathic connections it enables between our contemporary lives and those of people in the past.’

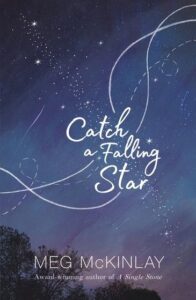

Meg McKinlay is a much awarded writer and poet of picture books, chapter books and young adult novels through to poetry for adults. She recently won the CBCA Picture Book of the Year award for How to Make a Bird illustrated by Matt Ottley. This year she was shortlisted for the Book Links Award for Historical Fiction for Children for her novel, Catch a Falling Star, where12-year-old Frankie faces old memories as Skylab falls to earth, creating an original fascinating historical context in which to place a deftly handled coming of age story.

Meg McKinlay is a much awarded writer and poet of picture books, chapter books and young adult novels through to poetry for adults. She recently won the CBCA Picture Book of the Year award for How to Make a Bird illustrated by Matt Ottley. This year she was shortlisted for the Book Links Award for Historical Fiction for Children for her novel, Catch a Falling Star, where12-year-old Frankie faces old memories as Skylab falls to earth, creating an original fascinating historical context in which to place a deftly handled coming of age story.

Meg kindly agreed to talk to StoryLinks about her approach to historical writing, saying that ‘I’m not really a historical fiction writer generally but I’ve tried to tap dance around that a bit.’

What is historical fiction to you and why do you write it?

I don’t actually think consciously about genre when I write. What I’m always doing is just following a story seed, a little kernel of inspiration, down whatever rabbit hole that might lead me. In the case of Catch a Falling Star, I began with my own childhood memories of Skylab falling from orbit; that event took place in 1979 so naturally that’s when I set the story, but I didn’t realise that qualified as historical fiction until after the book came out!

In terms of what historical fiction is to me, I guess I think of it as any creative response to, or relationship with, events from the past. My work tends to be very character-driven, and as both a reader and a writer, when I’m drawn to historical fiction, I think it’s because of the empathic connections it enables between our contemporary lives and those of people in the past. Whether that’s 1979 or 1879, it’s very easy to see the past as another country, its inhabitants somehow ‘other’, and I think fictional reimaginings can remedy that to some extent by stepping us into the skin of engaging characters, reminding us that people are people very much like us, no matter their context.

Why did you choose this particular time/topic?

Why did you choose this particular time/topic?

I was 11 when Skylab fell to Earth in July 1979 and I have vivid memories of that time, of the anxiety and uncertainty and the dawning reality that adults – even NASA scientists – can’t control everything. For me, that was an age when I was in that transitional space between childhood beliefs and reality, between the comforts of magical thinking and the at-times difficult truths about things. I think Skylab’s fall became a bit of a touchstone for those feelings, which is why, even though on one level Catch a Falling Star is a book about a space station, on another, it’s a character-focused coming-of-age story.

How do you reconcile truth and fiction in your historical writing?

‘Truth and fact can be quite different things.’

This was a real struggle for me. I had no idea where or how to draw the line between those two things. I did a lot of research and knew I wanted to be as accurate as possible about the Skylab story itself – the dates and technical aspects and dramatic developments. But what about other elements: did I need to stick rigidly to the actual dates and events of 1979 – to the weather and TV guide and starmap on certain days, to the school holidays? And what about setting? Skylab fell near Esperance in Western Australia but if I named Esperance in the narrative, wouldn’t I need to follow its then layout and streetscape and every other element besides?

In the end, for better or worse, I made a series of conscious choices about which elements to fictionalise and which to represent in historically accurate terms, and added a note in the book explaining these. Although the backdrop of Catch a Falling Star is an actual historical event, in the end what matters to me more is a kind of contextual and emotional truth. I didn’t need to – couldn’t have – represented Esperance itself, but I did need to evoke the sense of a small town in a similar setting. And while my characters and their actions are entirely fictional, I’d like to think I captured the truth of how a child might have responded to the real events taking place around them. It may sound odd, but I think truth and fact can be quite different things.

Who is your favourite writer of historical fiction? What is it about them that you admire?

For adult readers, I have been stunned by Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell series, for the incredible depth of her research and her complex and compelling evocation of characters and intricate relationships. For younger readers, one of my favourite books is Ursula Dubosarky’s The Red Shoe, which is set against the backdrop of the Petrov Affair, and is a beautifully written story which really brings the 1950s to compelling life.

What is next for you?

Nothing historical, I’m afraid! I’m finalising a couple of fun picture books called Ella and the Useless Day and How to Make a Bedtime; these are both illustrated by Karen Blair and will be out in 2022 and 2023 respectively. And I’m also working on a speculative fiction novel for older readers for which there are no definite plans at the moment.

Thank you Meg, for taking the time to talk to StoryLinks.

The winner of the inaugural Book Links Award for Historical Fiction for Children will be announced on Saturday 16 October from 4:00 – 4:45pm via ZOOM, free admission. Book here.

Mia Macrossan

Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Pingback: Meg McKinlay talks about writing historical fiction – Book Links QLD Inc