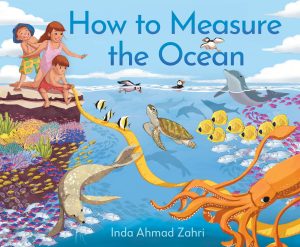

Inda Ahmad Zahri is an author, illustrator, surgical doctor and scuba diver. She was inspired to create this book when her daughter said, ‘What I love about numbers is that they go on and on and on forever.’

Inda Ahmad Zahri is an author, illustrator, surgical doctor and scuba diver. She was inspired to create this book when her daughter said, ‘What I love about numbers is that they go on and on and on forever.’ Zewlan Moor is the author of Nothing Alike and The Bill Dup. She is also a doctor and friend of Inda Ahmad Zahri

Zewlan Moor is the author of Nothing Alike and The Bill Dup. She is also a doctor and friend of Inda Ahmad ZahriError: Contact form not found.