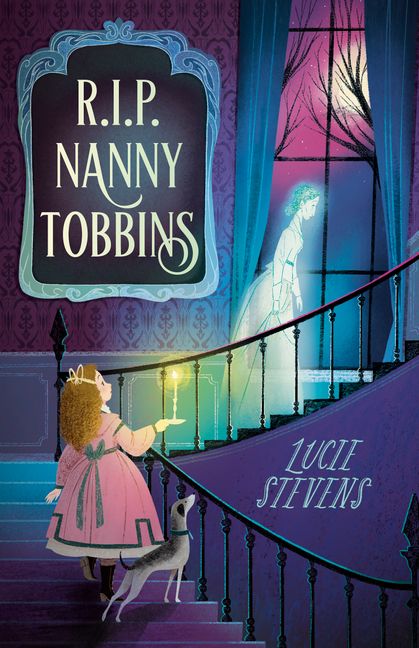

Meet Katrina Nannestad: Book Links 2023 Award for Children’s Historical Fiction Shortlist

By Mia Macrossan

There are four brilliant writers on this year’s Book Links Children’s Historical Fiction Award Shortlist:

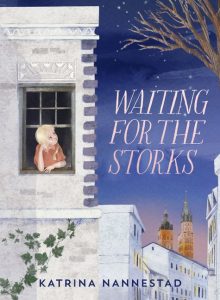

Felice Arena The Unstoppable Flying Flanagan, Katrina Nannestad Waiting for the Storks, Pamela Rushby Interned, and Claire Saxby – The Wearing of the Green

Each one has kindly agreed to answer a few questions about writing historical fiction for StoryLinks.

Today we interview Katrina Nannestad.

Today we interview Katrina Nannestad.

Katrina won the inaugural 2021 Book Links A ward for Children’s Historical Fiction with We Are Wolves and was shortlisted the following year for Rabbit, Soldier, Angel, Thief. This time she is shortlisted for Waiting for the Storks.

Judges’ comments: Young Polish Zophia is captured by the Nazis in WW II and forgets her true self living an idyllic life when adopted by a German family. Carefully and sensitively written, meticulously researched, the whole is a dissection the iniquitous Lebensborn program and of how the choices we make every day affect our lives and the lives of those we love.

Katrina is attending the Book Links online event on Wednesday July 19, where the winner will be announced. You can meet her and find out who the winner is by attending the online event on Wednesday 19 July, details here.

Katrina, thank you for talking to StoryLinks.

Why do you write historical fiction? Is it more difficult than writing your other books? (See Katrina’s website for all her other titles)

I find the whole process fascinating. I love the research because I’m always learning something new and having my ideas and understandings challenged. And I really enjoy the process of reducing big historical events to one character’s experience.

Writing historical fiction is far more difficult than writing my other books. The research is time consuming, and much of what I read is disturbing or overwhelming – not that it goes into my children’s books, but still, I’m exposed to it. I also feel a sense of responsibility in sharing stories that are inspired by things that happened to real people. I want to be honest and respectful, but I also need to make the stories accessible for young readers – age appropriate and entertaining. It’s a bit of a balancing act.

Why choose to write about the Lebensborn program?

We Are Wolves and Rabbit, Soldier, Angel, Thief were both set in eastern Europe and were about lesser-known aspects of the Second World War. It made sense that the third book would follow suit. My publisher gave me an article about Polish children who’d been stolen from their families during the war, and I was immediately fascinated. I knew children had been taken from Poland and the Soviet Union as slaves, but to learn that many had been stolen because of their Aryan features, then Germanised, was mind-boggling. The Nazis despised the Poles and yet they were stealing Polish children and pretending they were of pure German blood. The more I read about the Lebensborn Program and all that surrounded it, the more bizarre it seemed. This was one of those cases where truth is stranger than any fiction I could have created. Furthermore, there were disturbing echoes of other times and places where children had been stolen from their families and robbed of their identities, including in Australia. It felt like such a big, important story to tell. (It’s also the hardest story I’ve ever written!)

Certain fables are referenced often in Zofia’s story – The Fox and the Stork by Aesop, Hansel and Gretel and The Pied Piper. Why did you choose to use these?

I used Aesop’s fable, ‘The Fox and the Stork’, because it presents a very clear lesson: Actions have consequences. Cruel and selfish behaviour may benefit the perpetrator in the short term, but justice will catch up with them eventually. This fable also provides two very clear motifs that I use throughout the story – the Nazis as foxes, the Polish people as storks.

‘Hansel and Gretel’ and ‘The Pied Piper’ were chosen for the specific thoughts and feelings they would trigger in Sophia. (I don’t want to tell more or it might spoil the story!) But of course, they’re also culturally relevant – German fairy tales to match Sophia’s (Zofia’s) new German home and identity. Cultural details like stories, food, songs, celebrations, clothes, homes, schooling, all help to bring a setting alive in a story.

I looked at lots of other fables and fairy tales, but these were the chosen few – the perfect fit.

I found the characters of Zofia’s German adoptive parents very thought-provoking, especially her Vati. On page 312, you say this: “People are a jumble – good and bad, kind and mean, brave and cowardly, happy and sad. Nobody’s perfect. And nobody is entirely bad.” Authors are often told to ensure our main characters, our “good” characters, have flaws… but how do you go about ensuring your villains, your “bad” characters, likewise have redeeming qualities?

Zofia’s words are really echoing my own beliefs – that nobody is wholly good or wholly evil. We are all a complex jumble of feelings, motives, actions and beliefs.

I think villains are people who choose to do bad things – cruel and selfish things. Not just once, or on impulse, or because they’re forced to, but as a rule and because they believe it’s their right to do as they please at the expense of others. These people are all the more terrifying when they have likeable, relatable qualities. They’re not monsters who can’t help themselves. Wickedness is not their destiny. They’re regular people, like you and me, who choose evil.

Is there a point at which bad behaviour and bad choices turn a regular, flawed person into a villain? Is this point the same for all people in all situations, or does it change according to circumstance? Hmmm.

In war, there are people on both sides who are trying to be kind and humane, and people on both sides who will do unspeakably wicked things. I truly believe most people would rather be at home, living in peace with their loved ones, than fighting a war, but they get dragged into the misery by their leaders. Therefore, it makes sense to have many regular, likeable German characters in my story. Even the ones who have some icky beliefs are, on the whole, relatable. It’s back to that matter of degrees, isn’t it? Where is the tipping point for villainy? And how much can we attribute to indoctrination and the chaos and pressures of war?

Oooh, these are big issues to ponder. I do love a grey area!

This story is all about the choices in a person’s life, how everything we do is a choice and what we do when we don’t have a choice. Is this your way of challenging readers to think about our past and their future?

This follows along nicely from the last question!

We know that wartime changes the normal order of things and sometimes people make seemingly bad choices for good reasons. Or they make noble choices that have terrible consequences. We see this in comparing Zofia’s and Tomas’s paths during the war.

I think we can’t really understand the choices a person makes unless we know their whole story. Someone might appear to have made poor choices but perhaps that was the best available to them at the time. It’s easy to judge. Perhaps we should err on the side of compassion. (Unless they’re obviously villains! See the above question.)

By the way, the ‘Make a Choice’ game actually began as a way to add some light and fun to the narrative. But by Chapter 3, it became clear to me that the game was going to take a grander role in the story than I intended. It was like a character who takes on a life of its own and starts going off script.

With so many difficult topics being covered, what was the most surprisingly difficult thing to write about?

I was actually finished writing the book when I had this sudden terror that I was giving voice – a kind of platform – to words and beliefs that are despicable. Classifying children (or any humans) as desirable or unacceptable is disgusting. I believe all people are created equal and are precious regardless of race, culture or religion.

But of course, the whole reason the Lebensborn Program existed was because of this Nazi prejudice and their commitment to creating the perfect Aryan race, their belief in the need to keep German blood pure. It’s important that we acknowledge that these things happened, that they were immoral, and that we do not want them to be given a foothold again. I hope I have made it very clear that these were despicable and destructive terms.

Were there any scenes that you were unsure of keeping in the book due to their confrontational nature and the age of the target audience?

Yes, I wondered about the scene where the girls are forced to stand out in the frost, and the scene where Zofia is locked in the basement. These things – and far worse – really did happen to the kidnapped children. I felt they needed to be included to show how terribly these children were treated, but also to demonstrate the total lack of logic in the way this program was executed. If these children were believed to be of German blood, valued Aryans, the chosen ones, why were they treated with such cruelty and disdain?

Your bio at the end of the book says that you love “creating stories that bring joy or hope to other people’s lives”. Given that you were writing about such horrific subject matter in terms of the war in general and the Lebensborn program in particular, how did your aim of bringing joy and hope impact your decisions around how to end a story like this? You clearly had a range of options for how Zofia’s story could end.

I believe children (and most adults!) need stories to leave them with a sense of hope and satisfaction. After all Zofia had been through, I thought she’d earned a happy ending. And throughout her story, I think there is hope and joy in the way she offers friendship and support to those she meets, and is loved by others.

Despite the unspeakable tragedy wrapped up in the Second World War, we do find true stories of survival, resilience, hope, love, humour and incredible coincidences that lead to the reunion of loved ones. So I never feel like a happy ending is unforgivably forced. Who’s to say that my character isn’t one of the lucky ones?

You are obviously not afraid to tackle the darker side of human existence and you certainly excel at bringing it to children in a reassuring and accessible way. What’s next for you? Are you writing any more historical fiction? Can we expect a novel set in a WW II concentration camp?

My next historical novel is called Silver Linings and is inspired by something tragic that happened in my grandmother’s life. It’s a snapshot of Australian rural life in the 1950s and is, I think, filled with laughter, joy and iconic Aussie moments, despite the sorrow. It will be out in November.

I am currently writing a novel set in Bavaria during the Second World War. It’s about another tricky issue and I’m wondering if I’ve bitten off more than I can chew!

I don’t think I’ll write a story set in a concentration camp. There are many amazing stories written by actual survivors.

You are a prolific writer – do you write several novels at once – say a complex serious one such as Waiting for the Storks and alternate with a light-hearted one such as a Travelling Bookshop adventure, as a palate cleanser as it were? Or do you deep dive and stay on the one story?

I’m a deep diver. I can’t flit back and forth between books. I have to immerse myself in the one story. I take the journey with my characters, on and on without pause. I don’t know how to write any other way. Even when I stop writing a book to do school visits and festivals, I am thinking about the story – researching, waking at night and planning scenes, holding conversations with the characters in my head (or, embarrassingly, out loud!).

I love writing historical fiction but by the time I’m finished a book, I’m exhausted – and sometimes a little bit sad. Writing The Travelling Bookshop stories in between my historical novels is a pure delight. The travel, adventure and humour – and the anticipation of Cheryl Orsini’s gorgeous, joy-filled illustrations – is therapy!

Do you think that Zofia ever got her crimson velvet skirt made?

Absolutely – although I think Tata made it, not the other tailor. He would have put love, hope and gratitude into every single stitch.

Thank you so much Katrina, for taking the time to answer our questions. It is always fascinating to gain a deeper insight into a writer and her craft.

Go to Katrina’s website for other enjoyable historical novels, including We Are Wolves and Rabbit, Soldier, Angel, Thief and many other stories.